|

Juan José |

|

Good manzanilla is barrel-matured for up to forty years before it is ready for public consumption, and Spain seems intent on doing the same (sans barrel) for its best operas. It may not have had quite so long a wait in the wood as Albéniz´s Merlin, but though Pablo Sorozábal´s Juan José was written in 1968 this was its first Madrid performance, only two days after the world premiere in the composer’s native Donostia. The tangled tale of its cancellation whilst in rehearsal during Teatro de la Zarzuela´s 1979 season, with a cast which would have included Tomas Álvarez, Ángeles Chamorro and Enrique del Portal, is still debated more than twenty years after the composer’s death. Sorozábal maintained to the last that Juan José was the best of him, and now Madrid has had the chance to judge for itself.

Joaquín Dicenta’s tragedy Juan José (1895) is a milestone in Spanish drama, the theatrical equivalent of Pérez Galdós’s exposure of social wrongs in his Episodios nacionales novel sequence. Its plot of sexual jealousy, violence and murder is propelled by the fuel of unemployment, hunger and grinding poverty amidst Madrid’s poorest classes. Penniless labourer Juan José has his dignity, his work and ultimately his woman Rosa taken from him by the boss, Paco. Imprisoned for theft after stealing in order to stay with Rosa, he escapes and kills the pair of them, tamely giving himself up for lost as the curtain falls. The play was unsurprisingly eclipsed after the civil war, but its swift action and emotional power make for promising operatic material which Sorozábal exploits in the three tersely structured acts of his drama lírico popular.

The fractured, stop-go

conversational idiom brings Sorozábal’s earlier opera

Adiós a la bohemia to mind, although the harmonic

dress is closer to the astringencies of his post-war zarzuelas such as La

eterna canción. The writing is short-breathed, urgent and spare,

moments of lyrical expansiveness throttled almost before they can bloom.

Nothing is superfluous. Nothing is inflated. This is music living in the

moment, loosely bound by a batch of leitmotifs expressing milieus and

individual characters, each of whom is given their own distinctive orchestral,

melodic or rhythmic profile. The Celestina-like Isidra, for example,

continually badgering Rosa to accept which side her bread is buttered, is

associated with a driving, martial rhythm on cutting strings at almost every

appearance. Only the despairing hero seems murkily defined. Though never

sentimentalised his major utterances sound at first hearing more conventional

and less focussed than the majority of the score.

The fractured, stop-go

conversational idiom brings Sorozábal’s earlier opera

Adiós a la bohemia to mind, although the harmonic

dress is closer to the astringencies of his post-war zarzuelas such as La

eterna canción. The writing is short-breathed, urgent and spare,

moments of lyrical expansiveness throttled almost before they can bloom.

Nothing is superfluous. Nothing is inflated. This is music living in the

moment, loosely bound by a batch of leitmotifs expressing milieus and

individual characters, each of whom is given their own distinctive orchestral,

melodic or rhythmic profile. The Celestina-like Isidra, for example,

continually badgering Rosa to accept which side her bread is buttered, is

associated with a driving, martial rhythm on cutting strings at almost every

appearance. Only the despairing hero seems murkily defined. Though never

sentimentalised his major utterances sound at first hearing more conventional

and less focussed than the majority of the score.

Sorozábal being what he is, there’s no shortage of risk-taking, and episodes of shockingly brash vulgarity counterpoint the prevailingly sweet Puccinian popular idiom. It’s a bold score, and not easy to predict. How unpredictable, for starters, is Paco’s generous tenor ardour – unlike Dicenta’s original he is allowed to survive, as bosses do. Bad men don’t think themselves so, and Sorozábal has the ability of the experienced dramatist to trust his listeners rather than do their thinking for them. The near levity of the prison atmosphere in Act 3 may seem counter-intuitive, but provides exactly the right sense of physical relief needed to progress the drama and vary the gloom. There’s a multitude of neat orchestral interventions, most memorably a thin-toned, distant barracks trumpet heralding sour dawn after the final catastrophe.

It’s tempting to talk of “Spanish verismo”; but given the formal urgency and spartan means, the total effect to my ears is akin to mid-century German expressionism, more Wozzeck madrileño than La Boheme. But ultimately the method is very much this composer’s own. The middle act set in Rosa and Juan José’s slum dwelling has great emotional force, dominated by a contrapuntal string cantilena of almost Sibelian dignity, a gnawing rondo to evoke the occupants’ hunger. The opening scene for Rosa, her sympathetic friend Toñuela and the stone-hard Isidra is as moving as anything the composer ever wrote, striking a note of noble suffering quite new in his stage work. The pivotal dúo for Rosa and the despairing Juan José which follows is the heart of the drama, a blood-letting of the spirit which the last act murder confirms in the body.

Like Adiós a la bohemia, this is an opera which may only yield up its finer secrets after close and detailed listening. The text is set throughout in a most natural manner, and it’s vital to know precisely what is being said – something which wasn’t possible in the Auditorio Nacional, where the singers were occasionally overwhelmed by the committed exuberance of the Orquesta Sinfónica de Musikene, players short on years but long on virtuosic skill. The strings were particularly impressive, but there was some poetic work from the woodwind and brass soloists too. Jose Luís Estellés has moulded his young team into as impressive a band as I’ve heard in Spain, and their joint contribution was key to the evening’s success.

Juan José

got a generous crack of the whip as far as the soloists were concerned,

too. Ana María Sánchez endowed Rosa with all her

vocal splendours, commanding exquisite subtlety above the stave with pinging

penetration below it, a marvellous singer at the height of her powers. Not that

she missed out on characterisation: her switch from despair to bland

salon-sophistication in the last scene was chillingly girlish. Sánchez

was well supported in that superb central act by Olatz

Saitúa’s lighter Toñuela, and by the assured

Maite Arruabarrena, who precisely captured Isidra’s

driven practicality. Manuel Lanza was in good voice as Juan

José, mellifluous and taut throughout despite a tendency to sing just

under the note under pressure. José Luis Sola made the

most of Paco’s vocal sweetmeats and is clearly a name to watch, whilst

young bass Simón Orfila made an equally positive

impression as the hero’s prison mentor Cano, firm of tone and unfailingly

clear of diction. Emilio Sánchez provided luxury

casting in two minor roles, and only Celestino Varela’s

underpowered Andrés (Horatio to Juan José’s Hamlet) left

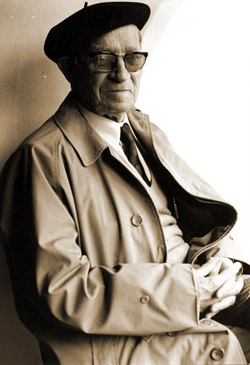

much to be desired. The projected montage of Madrid’s fin de

siècle poverty mixed with panned shots of Sorozábal’s

manuscript and the Maestro at work added nothing. The score was eloquent enough

not to need tiresome multimedia aid.

Juan José

got a generous crack of the whip as far as the soloists were concerned,

too. Ana María Sánchez endowed Rosa with all her

vocal splendours, commanding exquisite subtlety above the stave with pinging

penetration below it, a marvellous singer at the height of her powers. Not that

she missed out on characterisation: her switch from despair to bland

salon-sophistication in the last scene was chillingly girlish. Sánchez

was well supported in that superb central act by Olatz

Saitúa’s lighter Toñuela, and by the assured

Maite Arruabarrena, who precisely captured Isidra’s

driven practicality. Manuel Lanza was in good voice as Juan

José, mellifluous and taut throughout despite a tendency to sing just

under the note under pressure. José Luis Sola made the

most of Paco’s vocal sweetmeats and is clearly a name to watch, whilst

young bass Simón Orfila made an equally positive

impression as the hero’s prison mentor Cano, firm of tone and unfailingly

clear of diction. Emilio Sánchez provided luxury

casting in two minor roles, and only Celestino Varela’s

underpowered Andrés (Horatio to Juan José’s Hamlet) left

much to be desired. The projected montage of Madrid’s fin de

siècle poverty mixed with panned shots of Sorozábal’s

manuscript and the Maestro at work added nothing. The score was eloquent enough

not to need tiresome multimedia aid.

Juan

José was its composer’s youngest child, and its continued bad

luck was a cause of considerable bitterness to him during his final years.

Fitting then that the warmest applause was reserved for a gracious gesture from

the podium: at the end Estellés offered up the full score, first to the

audience and then to the huge projected image of the composer. It was a moving

moment, and a privilege to witness. Pablo Sorozábal´s magnum opus

had been heard in Madrid at last, and the reparation was of fit quality. But

make no mistake, its reception was no mere succès sentimental,

but a recognition of the appearance of that pearl beyond price – a

distinctive, theatrically viable full-length Spanish opera. On the strength of

this performance it surely will not take another 40 years for Juan

José to claim its rightful place, on the stage of the Teatro de la

Zarzuela.

Juan

José was its composer’s youngest child, and its continued bad

luck was a cause of considerable bitterness to him during his final years.

Fitting then that the warmest applause was reserved for a gracious gesture from

the podium: at the end Estellés offered up the full score, first to the

audience and then to the huge projected image of the composer. It was a moving

moment, and a privilege to witness. Pablo Sorozábal´s magnum opus

had been heard in Madrid at last, and the reparation was of fit quality. But

make no mistake, its reception was no mere succès sentimental,

but a recognition of the appearance of that pearl beyond price – a

distinctive, theatrically viable full-length Spanish opera. On the strength of

this performance it surely will not take another 40 years for Juan

José to claim its rightful place, on the stage of the Teatro de la

Zarzuela.

© Christopher Webber 2009

Juan José (Pablo

Sorozábal. Text by the composer, after Joaquín

Dicenta)

Cast: Manuel Lanza - Juan José; Ana María

Sánchez - Rosa; Maite Arruabarrena - Isidra; Olatz Saitúa -

Toñuela; Celestino Varela - Andrés; José Luis Sola - Paco;

Simón Orfila - Cano; Alberto Nuñez - Perico, Bebedor; Emilio

Sánchez - Tabernero, Presidario; Mario Cerdá, Iñigo Vilas,

Elena Barbé, Consuelo Garrés, Miren Urbieta - Amigos &

amigas; Constantino Romero - narrator.

Itziar Barredo - repetiteur; Ignacio

García - theatrical realisation (with Fernando Carmona); Carlos

Fernández Aransay - musical assessor

Orquesta Sinfónica de

Musikene, c. José Luis Estellés

![]() En español

En español![]() Pablo

Sorozábal (biography)

Pablo

Sorozábal (biography)![]() zarzuela homepage

zarzuela homepage

25/2/09